Hospital Calling for a Family Meeting to Discuss Cancer Diagnosis

- Written report protocol

- Open Admission

- Published:

Benefits and resource implications of family unit meetings for hospitalized palliative care patients: enquiry protocol

BMC Palliative Care volume 14, Article number:73 (2015) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Palliative care focuses on supporting patients diagnosed with avant-garde, incurable affliction; information technology is 'family centered', with the patient and their family (the unit of care) being cadre to all its endeavours. However, approximately xxx–50 % of carers feel psychological distress which is typically under recognised and consequently not addressed. Family unit meetings (FM) are recommended as a ways whereby wellness professionals, together with family carers and patients hash out psychosocial issues and programme care; however there is minimal empirical research to decide the net effect of these meetings and the resources required to implement them systematically.

The aims of this study were to evaluate: (1) if family carers of hospitalised patients with advanced illness (referred to a specialist palliative care in-patient setting or palliative care consultancy service) who receive a FM written report significantly lower psychological distress (principal effect), fewer unmet needs, increased quality of life and feel more prepared for the caregiving office; (2) if patients who receive the FM experience advisable quality of end-of-life care, as demonstrated by fewer hospital admissions, fewer emergency department presentations, fewer intensive care unit hours, less chemotherapy treatment (in last 30 days of life), and college likelihood of death in the identify of their choice and admission to supportive care services; (three) the optimal time point to evangelize FM and; (four) to determine the cost-benefit and resources implications of implementing FM meetings into routine practice.

Methods

Cluster type trial design with two style randomization for aims 1-iii and health economical modeling and qualitative interviews with health for professionals for aim 4.

Give-and-take

The research volition determine whether FMs have positive practical and psychological impacts on the family, impacts on health service usage, and financial benefits to the health intendance sector. This study volition also provide clear guidance on appropriate timing in the disease/intendance trajectory to provide a family coming together.

Trial registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12615000200583.

Background

Acute hospitals provide cease-of-life care to the majority of people who die in Australia and many other countries [1]. Palliative care focuses on supporting patients diagnosed with advanced, incurable affliction. Information technology is 'family unit centered', with the patient and their family considered to be the unit of intendance [2]. Given the pregnant burden associated with caring for a dying relative, the Globe Health Organisation (WHO) advocates that wellness care services focus on enhancing family members' quality of life [iii]. Appropriately, many nations have established standards and policies for responding to the needs of family carers as well every bit patients [4–6]. Despite these initiatives, patients with avant-garde disease may be exposed to ambitious or futile handling, and approximately 50 % of carers experience psychological distress, which is typically nether-recognised [7].

Advice with patients and their family is a vital element of palliative care. Information exchange, preparing for discharge and assessing needs is recommended standard practise. Only when carers of patients with advanced disease are well informed are they able to provide high quality terminate-of-life treat their relative [eight]. Inadequate communication can have profound negative effects resulting in psychological distress due to unmet information needs, lack of shared conclusion making and mistrust of healthcare providers [nine]. Open discussions between health professionals and family carers are an constructive manner of providing psychological support [10]. Nonetheless, the quality of communication can vary considerably and advice failures are the nearly common reason for complaints in wellness intendance, with end-of-life care being no exception [one]. Interventions with family carers which focus on responding to needs and preparing them for their office have produced demonstrable improvements in carer well-being and sense of preparedness [11, 12], reduction of unmet needs [11, 13–16], and carer burden and increased quality of life and knowledge of patient symptoms [17]. Findings from systematic reviews besides demonstrate that structured information from health professionals can reduce feet [18]. The benefits of family carer involvement in belch planning have likewise been reported [19].

Ane of the nigh of import clinical tools for healthcare providers to facilitate communication for people with avant-garde disease is a family unit meeting [twenty–22]. Family unit meetings (also known as family conferences), are meetings between the family carers, the patient (where possible) and health care professionals, and are undertaken for multiple purposes including psychosocial back up, clarifying the goals of care, discussing diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, belch planning and developing a plan of care for the patient and carer [23]. Studies on family unit meetings in intensive care units (ICUs) have demonstrated improvement in communication [twenty, 24], subtract in carer burden [25], and, importantly, reduction in length of stay [26]. Family meetings in the ICU have likewise led to measurable benefits including decreased mail service-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression [20, 27].

Family meetings are recommended as a core intervention within the context of palliative care provision [28]. These encounters, however, are not ordinarily provided consistently or systematically, nor are they conducted according to best available evidence [29]. Moreover, the specific outcomes for patients, family carers and health professionals associated with conducing a family meeting within the palliative care setting are underexplored.

Structured family unit meetings guidelines and pilot work

Hudson and colleagues adult clinical exercise guidelines [xxx] for conducting Structured Family Meetings (SFMs) for those patients referred to specialist palliative intendance in hospitals.

The meetings are intended to take no longer than one hour and should exist conducted by health care professionals with relevant preparation in facilitating such meetings. Hudson and colleagues subsequently examined the feasibility and effectiveness of the SFM clinical guidelines in an observational written report using mixed methods evaluation [31]. The following outcomes were demonstrated: (1) family carers reported significant reductions in unmet needs; (2) family carers reported that meetings were informative and useful; (three) wellness professionals reported that the meetings were well-facilitated and (four) family unit meeting facilitators (provided with specific training to convene and conduct a family unit meeting) reported that they were better equipped to facilitate the meetings. This study provided preliminary data on the feasibility and acceptability of family meetings every bit a means of identifying and addressing family concerns. These findings require farther testing in a larger sample, using more robust enquiry methods [31]. In addition, information technology would be advantageous to explore patient outcomes, define any sustained longer term benefits of SFM for family carers (focusing on distress) and discern the all-time time (within the advanced disease trajectory) to conduct family meetings.

In summary, whilst current guidelines abet family unit meetings be routinely conducted for all patients [28], these encounters are typically neither consistently provided nor conducted according to best available evidence. There is therefore justification to further investigate, within a robust inquiry evaluative written report design, the impacts and outcomes of SFM for patients, carers and families and the barriers and enablers that may influence effective implementation. Given the major financial and resource implications of SFM, we will also provide articulate guidance on the advisable timing in the disease/intendance trajectory to provide a family meeting.

The purpose of this project is to evaluate outcomes for patients and family carers who nourish a SFM and determine the cost and resources implications of implementing SFM into standard practice for hospitalised patients with avant-garde affliction.

Our aims are:

- one.

To appraise the short and longer term effect of SFM on patient and family unit carer outcomes and determine the most appropriate time point in a patient's advanced disease trajectory to provide a SFM.

- 2.

To decide the cost-do good and resource implications of implementing SFM meetings into routine exercise.

Methods

The following sections item the methods for addressing each of the projection aims.

Aim i

To assess the short and longer term result of SFM on patient and family outcomes and determine the virtually appropriate fourth dimension point in a patient'due south disease trajectory to provide a SFM.

Our alternative hypotheses for Aim 1 are:

-

(H1) Family carers of hospitalised patients with advanced disease (referred to a specialist palliative intendance in-patient setting or palliative intendance consultancy service) who receive a SFM will report significantly lower psychological distress (primary outcome), fewer unmet needs, increased quality of life and feeling more prepared for the caregiving part.

-

(H2) Patients who receive the SFM will feel appropriate quality of end-of-life intendance, as demonstrated past fewer infirmary admissions, fewer emergency section (ED) presentations, fewer intensive intendance unit hours, less chemotherapy treatment (in final xxx days of life), and higher likelihood of death in the place of the person's choice (in consultation with their caregivers) and access to supportive care services.

-

(H3) Patients and family carers who receive a SFM earlier in their advanced disease trajectory (i.due east farther way from death) will have more favourable outcomes (equally per outcomes listed in H1 and H2).

Research design

This written report will randomise three participating sites: all sites will collect baseline data (i.e. Time 1, ii & 3 data) for six months; then 2 of the three sites will evangelize the intervention. As such, 1 site volition remain the control site for the entire time and there will exist before and after measurements (with excellent baseline data collected prospectively) for the two sites which will participate in the intervention. As each site will have baseline information, any differences between sites tin can exist identified and, if necessary, controlled for during the analyses. The intervention recruitment period is longer than the control period in the two intervention sites to ensure that the total numbers of control and intervention participants are approximately equivalent). This blueprint was deemed the most appropriate and feasible method for this type of wellness service research, since randomisation by patient in each service risks cross-grouping contagion within that clinical setting. A conventional cluster trial or stepped-wedge pattern is not feasible due to the meaning number of sites that would be required. Sites will be randomised by an independent statistician via a random number generation arrangement.

Participants

Inclusion criteria for patients

Hospitalised patients with advanced, non-curable disease referred to a specialist palliative intendance in-patient unit of measurement or palliative intendance consultancy service for inpatients, who have a person (relative or friend) whom they perceive to exist their principal back up person (i.east primary family carer), who are willing for the enquiry squad to approach the family unit carer for potential research participation and agreeable to accept their medical information shared with the family unit carer, if pertinent, during the SFM. Exclusion criteria for patients: Nether 18; probable to die inside i week (equally assessed by treating physician or senior nurse); unable to identify a primary family carer, unable to provide informed consent due to cognitive impairment or incapacity to comprehend and speak English (every bit assessed by treating md, senior nurse or enquiry assistant).

Inclusion criteria for family carers

Nominated by the patient as their primary support person and willing to attend a SFM if allocated to the intervention arm.

Exclusion criteria for family carers

Nether 18; incapacity to understand or speak English; unable to provide informed consent due to cognitive impairment (as assessed by the research assistant); or not amusing to existence considered the primary family carer.

For the intervention phase, patients and family carers who accept already been involved in a formal family coming together every bit part of routine specialist palliative care volition be excluded from participation. As function of routine data collection for the study we will ask each participating site to record in the medical tape if a formal family meeting (ie specific meeting set up to ostend plan of care) has occurred.

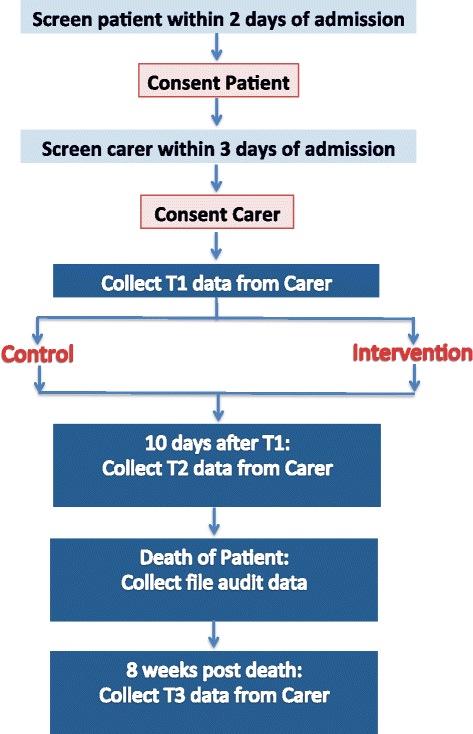

Procedure

Recruitment (see Fig. 1) will occur equally presently as possible (inside 48 h) after the patient is admitted to the palliative care unit or seen by the consultancy service. The research assistant will screen the list of new admissions to both the inpatient unit and the consultative squad daily and speak with the clinical team to check eligibility. They will arroyo eligible patients in person within 48 h of access to give patients a copy of the Plain Linguistic communication Statement and consent form and invite patients to participate. Patients will need to consent to their medical records beingness accessed and their medical details being discussed at the family unit meeting (if well enough and if allocated to the intervention group). Patients will need to identify a family carer (as per inclusion criteria) and provide consent for the research assistant to contact them about the written report. Patients will not exist required to provide any cocky-report data.

Recruitment and data collection

The enquiry banana will then telephone the family carer (or approach them in person at the hospital) to invite them to participate inside 72 h of patient admission (see Fig. 1). The enquiry assistant volition requite the family unit carer a copy of the Plain Language Statement and consent grade if approaching them in person and go through it with them and obtain formal written consent. If contact has been made by phone, the research assistant will get through the content of the Plain Language Argument and consent class with them over them phone and ship it to them (either by email or postal service) to be signed and returned past post or in person. Once the carer has consented, the research banana volition arrange a user-friendly fourth dimension (and place) to collect time 1 information either over the phone or in person (at the hospital). Time 1 data collection will take no longer than 30 min to consummate and volition be conducted within 1 week from referral/access.

The enquiry banana will phone the family unit carer when it is time to collect fourth dimension 2 and 3 data and ask them if they would prefer to complete the questionnaire over the phone, in person at the hospital, or by post. Times two and three data collection will take no longer than 30 min to complete.

If the family unit carer is in the intervention group, the inquiry assistant will refer them to the family coming together facilitator (who has been trained to conduct the structured family meetings) as soon as the carer has completed time1 data. Similarly, one time the family meeting has been conducted (ideally within a week of time one information being collected) the family meeting facilitator will inform the research assistant. This written report blueprint does not allow the research assistant to be blinded to the condition to which carers are allocated.

If the family carer is in the control grouping, and so they receive usual intendance for the period between fourth dimension ane and fourth dimension 2 data collection.

Standard intendance

Standard care is known to be quite heterogeneous. Family meetings are offered in all participating sites only the frequency and method of conduct varies; thus nosotros are mindful that some control participants volition receive a family meeting, although these are typically not formally structured. Our research has been designed in recognition of this and nosotros volition besides collect data on the frequency of family unit meetings conducted in the control grouping.

Intervention

The intervention which is administered according to clinical guidelines for conducting family unit meetings is comprehensively outlined in the before piece of work of Hudson and colleagues [32]. In summary, the guidelines incorporate: (i) principles for conducting family meetings; (2) pre-coming together procedures such as liaising with the patient/family and prioritising bug; (3) deciding who needs to attend the family meeting; (4) a procedure for conducting the meeting; and (5) strategies for follow upwards afterward the meeting, including data on whether or not the priority bug for the family carer have been addressed. The meetings are intended to have no longer than one hour.

Approximately four facilitators volition be appointed at each of the participating sites to convene and conduct the family unit meeting/intervention. The facilitators will exist nurses, doctors, social workers or psychologists with all-encompassing clinical palliative intendance experience and relevant academic qualifications. Facilitators volition be identified by the director of palliative care at each of the participating sites. They will receive training in administering the intervention which will incorporate conducting the family meeting according to the aforementioned guidelines; along with communications skills theory and practicum. In order to limit variation of intervention delivery at each site the training arroyo for all facilitators will be consistent and will be conducted face to face over the course of 1 day.

Data collection

Eligibility data volition exist recorded along with reasons for refusal to participate (for those eligible who are willing to provide this data). Data collection will involve mixed methods including quantitative and qualitative data.

Family carer measures

We have administered similar quantity and blazon of measures to family caregivers with no negative sequelae apparent [33].

- (i)

The 12 item version of Full general Health Questionnaire (GHQ) [34]. The GHQ has demonstrated good reliability and validity and is commonly used as a screening tool to detect those likely to develop psychiatric disorders. It is a measure of the mutual mental health problems including the domains of low, anxiety, somatic symptoms and social withdrawal [35, 36]. The GHQ is scored on a Likert scale, with a maximum score of 36; score ≥15 indicates evidence of distress; and score >20 suggests astringent issues and psychological distress. Family unit carers who run into the cutting off for profound psychological distress (>20) at T1 will exist advised of such and recommended that they seek formal medical/psychological review from their treating medico or palliative care team. They will however notwithstanding be eligible to participate in the report. GHQ volition be administered at all three fourth dimension points.

- (2)

The Family Inventory of Needs (FIN) [37] has 20 items and has been shown to take good reliability and validity [37, 38] . Administered at times i and two only as this focuses on caregiving while the patient is alive.

- (3)

The Preparedness for Caregiving Calibration (PCS) [39] has viii items and has been shown to have proficient reliability and validity [38] . Administered at times 1 and two only as this measure focuses on caregiving while the patient is live.

- (4)

The Short class health survey version two (SF12-v2) is 12 items quality of life measure that has been widely used across many diverse populations. It is a measure of both physical and emotional quality of life [40]. Administered at all three time points.

- (five)

The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) calibration is a measure of caregiver quality of life. The scale has been establish to exist a reliable and valid measure of quality of life for caregivers of cancer patients and cancer patients receiving palliative care [41]. Every bit the questions do not specifically relate to cancer, they are appropriate for caregivers of non-cancer palliative care patients. Administered at times 1 and two but as this measure out focuses on caregiving QOL while the patient is alive.

- (6)

Family unit carers volition also complete a socio-demographic survey including details and level of function of their relative via the Australian Karnofsky scale [42]. Administered at T1 just.

- (7)

At time iii (after death) the family unit carer will likewise complete a measure of the quality of the decease which will exist measured using a shortened version of the Quality of Expiry and Dying Questionnaire [43, 44]. This mensurate has been widely used with like populations and includes 17 items that measure out different aspects of the dying feel.

We will also collect data on the appointment of patients' death to help with determining the impact of having the family unit coming together further away from death.

File audit (Patient record)

For the second hypothesis (H2), data will exist collected from the patients' medical records using a File Audit Checklist and also from data from the hospital authoritative data sets (which include ICD-10-AM codes which are collected for the Department of Wellness). These data volition include indicators of quality end-of-life care [45]: hospital admissions and length of stay, ED presentations, hours in ICU, chemotherapy administration in the last 30 and fourteen days of life, a new regimen of chemotherapy in last xxx days of life, and place of death. Data will also be collected on access to supportive care services, evidence of avant-garde care plans, and attendance at family meetings.

Sample size, power calculation and feasibility

The chief result for H1 is measured via the GHQ, a 12-particular scale with a possible range of 0-36. Our previous study [46] of 275 family unit carers in which the mean GHQ difference was 2.8 (SD = 5.6), represents a medium consequence size (ES) of 0.v which is a common gauge of a minimal important difference [47]. The sample size calculations are based on a smaller mean divergence between groups of 2.four, as some carers in the control group will accept family meetings equally part of standard care. Estimated sample size for ii-sample comparison of means Exam Ho: m1 = m2, where m1 is the mean in population 1and m2 is the mean in population 2 is 97 per grouping (full due north = 194). This calculation assumes that alpha = .05 (two sided), power = .90 (90 %), m1 = xvi.eight, m2-xiv, sd1 = vi, sd2 = 6, n2/n1 = 1.00. This sample size allows for sub-grouping analyses of the consult service compared to the inpatient service or other similar sub-grouping assay.

For the three recruitment sites, we take approximately 1900 palliative care inpatient admissions per twelvemonth and 3000 palliative intendance consult service admissions per twelvemonth. However, many consult service admissions become inpatient admissions. Approximately a 3rd of the total admissions per yr would exist both consult admissions and inpatient admissions, leaving 3280 admissions per twelvemonth that reverberate split up individuals. Based on eligibility rates and response rates of similar previous studies we can assume fifty % of these are eligible (due north = 1640), ineligibility mostly due to being imminently dying. A further 33 % of those who are eligible consent to participate (n = 546). Of the 546 that consent, we assume that 60 % volition complete information collection at Time 1 (due north = 327). Assuming 30 % attrition at T2 (leaving n = 228) and 50 % attrition at T3 (since it is during bereavement, attrition may be quite high), 114 cases can be completed per year, providing the required sample size of 228 from the recruitment pool in 2 years.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance has been obtained at each of the participating hospitals: St Vincent's Infirmary Melbourne, Austin Health, Melbourne Health - Commonwealth of australia. The trial has also been registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Group ACTRN12615000200583.

Analyses programme

The main analyses will be performed on pooled information beyond sites for the intervention and control groups, following an analysis of the baseline data to identify any differences between sites. Nosotros volition undertake analyses every bit follows. Summary statistics will be calculated to compare the characteristics of carers in each grouping. Linear mixed models volition be used to (one) compare patterns of modify over fourth dimension by testing the intervention group by time interaction and (2) estimating and testing differences in scores between groups at T2 and at T3 via linear contrasts, and accounting for the non-independent nature of the data in clusters. Mixed models yield unbiased estimates for data which are missing [48], and is relevant for cluster trials [49]. Sub analyses will be undertaken dependant upon obtaining a suitable sample size. In the event of 'no intervention effect', where possible, a sub-analysis will be conducted to compare outcomes in the control group carers who did non have a meeting (i.e. a 'per protocol' analysis) with those in the intervention group carers who had a coming together. In the event of 'no intervention issue' , a sub-analysis volition be conducted on those that were moderately or highly distressed at time 1 to compare outcomes in the control group and intervention group for distressed carers. A sub analysis will also be undertaken to explore any differences in outcomes betwixt participants recruited from the specialist palliative care in-patient facility and those recruited from a palliative care hospital consultancy service.

Aim 2

To determine the cost-benefit and resources implications of implementing SFM meetings into routine exercise.

Health economic modeling will be practical to estimate the toll-benefit of SFM. Determination assay [50] will be used to compare the downstream consequences of SFM versus standard of intendance, by extrapolation of efficacy data from the trial. The incorporation of Markov [51] and life-tabling [52] techniques will allow for the modeling of outcomes across the duration of the trial. The key output in cost-benefit analyses is net costs, comprising the costs of SFM minus costs saved from the reduction in downstream health services utilisation. Only direct healthcare costs will exist measured, and from the perspective of the Australian healthcare system. These will predominantly exist costs of inpatient and outpatient hospital care, medications and community-based healthcare services. All wellness economic analyses will exist undertaken in accordance with recommended approaches, such as 5 % discounting of estimated hereafter costs and health gains. To account for whatsoever doubtfulness in the data, inputs for wellness economic modeling, sensitivity and doubtfulness analyses volition be undertaken via Monte Carlo simulation [53].

We will also conduct a process evaluation to determine the resource requirements of administering the SFM. Such information will include the mean time to conduct the intervention, the number and the types of wellness disciplines involved in the family coming together and whether or not the patient too participated. We will besides explore the administrative time involved in setting up and facilitating the SFM.

At the completion of the intervention stage 2 focus groups will be conducted with wellness professionals and interviews (approx. 20) with family carers from the intervention sites volition be undertaken to explore the perceived impacts and benefits of the SFMs. They will also be used to discern external and internal policy changes; clinician (staff resource, beliefs and attitudes), patient and carer factors (access, timeliness, understanding, information). This will assist with monitoring temporal bug relevant to the report.

All health professionals at each of the two intervention sites who have attended at to the lowest degree ii of the SFMs volition be invited to participate in a focus group (via a personalised email). The Plainly Language Statement and consent form volition be attached to the email. At the beginning of the focus group, the project officer will go through the Plain Language Argument; which will provide all potential participants with the balls that their involvement is entirely voluntary and their participation or otherwise will in no fashion hinder their employment. Health professionals volition be asked to complete the consent form. Once informed consent is obtained from the palliative care health professionals, the project officer will conduct a focus group. The focus group will be taped and transcribed and any identifying information deleted from the transcripts. The focus group will take virtually thirty–60 min.

One in six family carers who complete the intervention will exist invited to participate in an interview after the completion of their time 2 questionnaires via a question on the questionnaire with a Yes/No response format and an open-ended space which requests a telephone number and best time to call. The research assistant will and then call the family carer at the suggested time and ask the carer whether they are notwithstanding interested in participating in an interview and if they are, they will organise a convenient time. Interviews may be conducted at the hospital or over the telephone. Interviews volition exist recorded and transcribed. A semi structured interview guide has been developed past the project squad and incorporates questions related to: perceptions of the way the family meeting was convened and conducted; reflections on any positive or negative outcomes and recommendations for improving family meetings. Information technology is expected that the interview take approximately thirty min.

Focus groups will be recorded and transcribed and analysed for impacts, benefits and additional content. Interviews will be recorded digitally verbatim and transcribed. NVivo software will be used to assistance with storage and coding. The interviews will be analysed using the five steps of thematic analysis recommended by Boyatzi [54] (1) reducing the raw information, (two) creating a code, (iii) determining the reliability of the code, (4) identifying themes within subthemes and (5) comparing themes across subsamples. The first two interviews (20 %) from each site volition exist coded by two members of the enquiry team. A Kappa value of 0.half dozen–0.viii indicating substantial agreement between raters [55] volition be achieved at pace 3 prior to the inquiry assistants completing steps 4 and 5 for the residue of the interviews.

Study fidelity

One in half-dozen intervention meetings at each site will be selected for transcription and assay to check fidelity of the intervention delivery method; and we will also record information almost the attendees and topics discussed and subsequently (a subsequent study) analyse the recordings with respect to a range of factors including the process of communication between the carer, patient and wellness professionals. Agreement the content and dynamics of family meetings will further inform implementation.

Give-and-take

The WHO advocates that palliative care should not only ameliorate the quality of life for patients but likewise for their families [iii]. The principle of family centred care and the inclusion of family carer satisfaction with terminate-of-life health care is advocated as a cardinal indicator of hospital functioning [56]. Electric current guidelines advocate family meetings to be routinely conducted for all patients [28] which has major financial and resource implications. These encounters all the same are typically non consistently provided nor are they conducted according to best available show. The research described herewith volition determine whether SFMs accept positive applied and psychological on the family unit, impacts on wellness service usage, and financial benefits to the wellness care sector. This study will also provide clear guidance on appropriate timing in the illness/intendance trajectory to provide a family meeting.

References

-

Australian Commission on Condom and Quality in Wellness Care (ACSQHC). Safety and quality of terminate-of-life care in acute hospitals: A background paper. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2013. p. 56.

-

Hudson P, Payne S. Family caregivers and palliative intendance: Current status and agenda for the time to come. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(7):864–9.

-

World Health Organisation (WHO). National cancer control programmes: Policies and managerial guidelines. second ed. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2002. p. 180.

-

National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-scientific discipline conference statement on improving end of life care, vol. 21. Kensington: National Institutes of Health; 2004. p. 32.

-

Palliative Care Commonwealth of australia. Standards for providing quality palliative intendance for all Australians. Canberra: Palliative Care Australia; 2005. p. 44.

-

National Constitute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guidance on cancer services: Improving supportive and palliative intendance for adults with cancer. The transmission. London: National Found for Clinical Excellence; 2004. p. 209.

-

Ziegler L, Loma K, Neilly L, Bennett MI, Higginson IJ, Murray SA, et al. Identifying psychological distress at key stages of the cancer affliction trajectory: A systematic review of validated self-study measures. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):619–36.

-

Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson HG, Schulman-Light-green D, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Bradley EH. Communication betwixt physicians and family caregivers well-nigh care at the end of life: When do discussions occur and what is said? J Palliat Med. 2005;8(6):1176–85.

-

Boyle DK, Miller PA, Forbes-Thompson SA. Communication and end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Patient, family, and clinician outcomes. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2005;28(4):302–16.

-

Hannon B, O'Reilly V, Bennett K, Breen One thousand, Lawlor P. Meeting the family: Measuring effectiveness of family meetings in a specialist inpatient palliative care unit of measurement. Palliat Support Care. 2012;ten(one):vii.

-

Hudson P, Remedios C, Thomas K. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for family carers of palliative intendance patients. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;9(i):17.

-

Eagar Yard, Owen A, Williams K, Westera A, Marosszeky N, England R, et al. In: Evolution CfHS, editor. Effective caring: A synthesis of the international evidence on carer needs and interventions. Brisbane: University of Wollongong; 2007. p. 114.

-

Northouse L, Katapodi M, Song Fifty, Zhang L, Mood D. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–39.

-

Hudson P, Thomas K, Quinn K, Cockayne Thou, Braithwaite One thousand. Didactics family carers near home-based palliative care: Final results from a grouping education program. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(ii):299–308.

-

Hudson P, Aranda S, Hayman-White K. A psycho-educational intervention for family caregivers of patients receiving palliative intendance: A randomised controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;xxx(4):329–41.

-

Hudson P, Aranda S. The 'Melbourne family support program (FSP)': Evidence based strategies that prepare family carers for supporting palliative care patients. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013.

-

McMillan SC. Interventions to facilitate family caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8 Suppl 1:S132–ix.

-

National Chest Cancer Centre and National Cancer Command Initiative. Clinical practise guidelines for the psychosocial intendance of adults with cancer. Camperdown: National Breast Cancer Center; 2003. p. 246.

-

Pearson P, Proctor S, Wilcockson J, Allgar V. The process of hospital discharge for medical patients: A model. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(5):496–505.

-

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Rubenfeld GD. The family conference as a focus to improve advice near end-of-life care in the intensive care unit of measurement: Opportunities for comeback. Crit Intendance Med. 2001;29(ii Suppl):N26–33.

-

Weissman D, Quill T, Arnold R. The family meeting: Starting the conversation #223. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(2):204–5.

-

Embankment WA, Anderson JK. Advice and Cancer? Part Ii: Chat Assay. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2003;21(iv):1–22.

-

Moneymaker K. The family briefing. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(ane):157.

-

Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family unit conferences in the intensive care unit of measurement. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(half-dozen):1679–85.

-

Lautrette A, Ciroldi M, Ksibi H, Azoulay E. End-of-life family conferences: Rooted in the evidence. Disquisitional Care Medicine. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S364–72.

-

Ahrens T, Yancey V, Kollef M. Improving family communications at the end of life: Implications for length of stay in the intensive care unit and resources use. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12(4):317–23. discussion 324.

-

Powazki R, Walsh D, Hauser K, Davis MP. Communication in palliative medicine: a clinical review of family conferences. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(10):1167–77.

-

Hudson P, Remedios C, Zordan R, Thomas 1000, Clifton D, Crewdson Grand, et al. Guidelines for the psychosocial and bereavement support of family caregivers of palliative care patients. J Palliat Med. 2012;xv(6):696–702.

-

Payne S, Hudson P. Assessing the family and caregivers. In: Walsh D, Caraceni A, Fainsinger R, Foley M, Glare P, Goh C, Lloyd-Williams Grand, Olarte J, Radbruch 50, editors. Palliative Medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008. p. 320–five.

-

Hudson P, Quinn K, O'Hanlon B, Aranda S. Family unit meetings in palliative care: Multidisciplinary clinical practice guidelines. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;19(vii):12.

-

Hudson P, Thomas M, Quinn K, Aranda S. Family meetings in palliative intendance: Are they effective? Palliat Med. 2009;23(two):150–vii.

-

Hudson P, Quinn Thou, O'Hanlon B, Aranda Southward. Family meetings in palliative care: Multidisciplinary clinical exercise guidelines. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7:12.

-

Hudson P, Thomas K, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D. Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on kickoff of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):522–34.

-

Goldberg D, Williams P. Manual of the full general health questionnaire. Windsor: NFER Publishing; 1978.

-

Jackson C. The general wellness questionnaire. Occup Med. 2007;57(1):79.

-

Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius Due north, Ustun TB, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, et al. The validity of 2 versions of the GHQ in the WHO written report of mental illness in general wellness care. Psychol Med. 1997;27(one):191–vii.

-

Kristjanson LJ, Atwood J, Degner LF. Validity and reliability of the family inventory of needs (FIN): Measuring the intendance needs of families of advanced cancer patients. J Nurs Meas. 1995;iii(2):109–26.

-

Hudson P, Hayman-White Grand. Measuring the psychosocial characteristics of family caregivers of palliative care patients: Psychometric properties of nine self-report instruments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(iii):215–28.

-

Archbold P, Stewart B, Greenlick M, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness every bit predictors of role strain. Res Nurs Health. 1990;thirteen:375–84.

-

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Curt Form Health Status Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and detail option. Med Intendance. 1992;30(half-dozen):473–83.

-

Weitzner MA, McMillan SC. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) Scale: revalidation in a home hospice setting. J Palliat Care. 1999;15(ii):13–20.

-

Abernethy AP, Shelby-James T, Fazekas BS, Forest D, Currow DC. The Australia-modified Karnofsky Functioning Condition (AKPS) calibration: A revised scale for gimmicky palliative intendance clinical practise. BMC Palliat Care. 2005;4:7.

-

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Norris Thousand, Asp C, Byock I. A measure of the quality of dying and expiry: initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2002;24(1):17–31.

-

Downey L, Curtis JR, Lafferty Nosotros, Herting JR, Engelberg RA. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. J Hurting Symptom Manage. 2010;39(one):9–22.

-

Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: Is information technology a quality-of-intendance upshot? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(23):3860–6.

-

Hudson P, Trauer T, Kelly B, O'Connor M. Improving the psychological wellbeing of family caregivers of home based palliative care patients: a randomised controlled trial. National Heath and Medical Research Council - Last report. Canberra: National Heath and Medical Inquiry Council; 2011.

-

Cohen J. Statistical ability analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Assembly; 1988.

-

Schulz K, Altman D, Moher D. Consort 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Br Med J. 2010;340:c332.

-

Campbell M, Elbourne D, Altman D. Espoused statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. Br Med J. 2004;328(7441):702–8.

-

Lilford RJ, Pauker SG, Braunholtz DA, Chard J. Conclusion analysis and the implementation of enquiry findings. BMJ. 1998;317(7155):405–nine.

-

Briggs A, Sculpher M. An introduction to Markov modelling for economic evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;thirteen(four):397–409.

-

Wesley D. Life tabular array analysis. J Insur Med. 1998;30(4):247–54.

-

Briggs AH. Handling dubiety in cost-effectiveness models. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;17(5):479–500.

-

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code evolution. Sage. 1998.

-

Guyatt G, Rennie D. JAMA Users' guide to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clincial exercise. Chicago: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2002.

-

National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission (NHHRC). Beyond the blame game: Accountability and performance benchmarks for the next Australian health care agreements. Canberra: National Wellness and Hospitals Reform Committee; 2008. p. 53.

Acknowledgements

Victoria Cancer Agency and Palliative Care Enquiry Network (Victoria).

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

1) PH, AG, GM, JP, DP, DC, DL, KT, BL, JM, CB; take made substantial contributions to formulation and design; 2) PH, AG, GM, JP, DP, DC, DL, KT, BL, JM, CB; have been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for of import intellectual content; 3) PH, AG, GM, JP, DP, DC, DL, KT, BL, JM, CB; have given concluding approval of the version to be published; 4) PH, AG, GM, JP, DP, DC, DL, KT, BL, JM, CB; agree to be accountable for all aspects of the piece of work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of whatsoever part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/four.0/), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zip/i.0/) applies to the data made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Hudson, P.L., Girgis, A., Mitchell, G.Thou. et al. Benefits and resource implications of family meetings for hospitalized palliative care patients: research protocol. BMC Palliat Care fourteen, 73 (2015). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12904-015-0071-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12904-015-0071-6

Keywords

- Palliative

- Family meeting

- Family conference

- Family carers

- Family caregivers

- Intervention

- Trial

- Wellness economic science

- Quality of life

- Unmet need

Source: https://bmcpalliatcare.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12904-015-0071-6

0 Response to "Hospital Calling for a Family Meeting to Discuss Cancer Diagnosis"

Post a Comment